Research Interest

(Last update: January 30, 2026)

My Motivation and Research

Scientific Motivation

My fundamental scientific motivation is to understand the dark side of the Universe — namely dark energy and dark matter, which together constitute about 95% of our Universe. Rather than treating modified gravity as a mere extension of General Relativity, I regard it as a powerful theoretical framework that may offer a deeper and more unified perspective on these mysterious components beyond the standard ΛCDM paradigm. This motivation underlies all of my research activities described below.

Research Directions

Building on the general perspectives outlined above, my research on modified gravity focuses on several interconnected directions that span both theory and phenomenological applications:

- Late-time Universe and Dark Energy: Investigating how modified gravity can explain the observed cosmic acceleration without invoking an extremely fine-tuned cosmological constant, and characterizing the theoretical predictions for late-time cosmology.

- Early Universe Cosmology: Exploring the implications of modified gravity models in the early Universe, including potential effects on inflationary dynamics and the Hubble tension.

- Astrophysical Applications: Applying modified gravity theories to compact objects and astrophysical structures, such as mass-radius relations of neutron stars and small-scale structure problems.

- Particle Physics and Quantum Gravity Interfaces: Studying how new degrees of freedom arising from modified gravity relate to particle-like excitations beyond the Standard Model and how such frameworks may inform bottom-up approaches to quantum gravity.

Overview

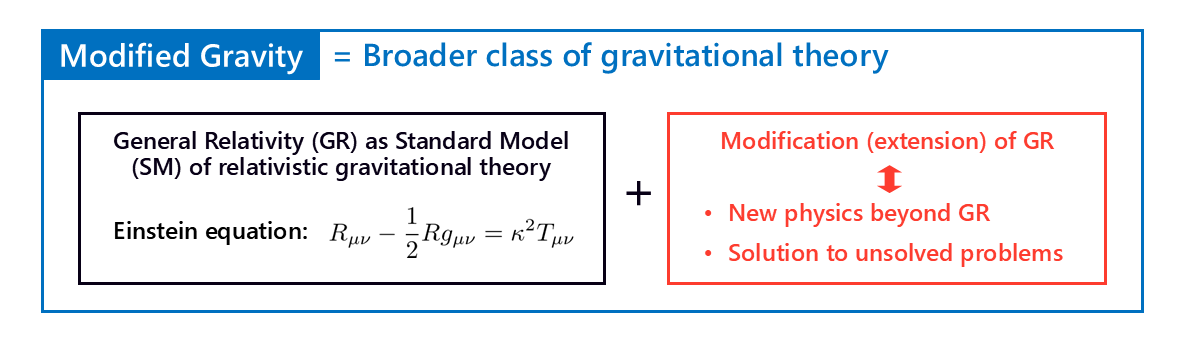

My research focuses on theoretical studies of gravitational theories that go beyond General Relativity (GR), which is called modified gravity theory. Modified gravity refers to frameworks that extend or generalize GR by adding new mathematical terms, introducing additional fields, or reformulating foundational principles. Over the years, many such modified gravity theories have been proposed and actively studied. This research aims to understand not just the formal structures of these theories, but also their physical implications.

GR is built on several foundational assumptions:

- four-dimensional spacetime,

- invariance under general coordinate transformations,

- a metric formulation of gravity, and

- field equations of second order in derivatives.

Any modified gravity theory generally predicts deviations from the predictions of GR. These deviations arise from the new structure introduced in the theory. If such deviations were observed in experiments or astrophysical data, they would provide evidence supporting modified gravity. Conversely, the absence of deviations places constraints on these theories and can rule out certain models.

Therefore, a key objective in this research is to identify measurable quantities , such as cosmological expansion histories and gravitational wave signals, and to compare their theoretical predictions with precise observational data. This approach, known as phenomenology, is essential for understanding which theory best describes gravity in our Universe.

Modified gravity theories may also give rise to new physical phenomena that cannot be explained by GR alone. Such phenomena could offer solutions to unresolved issues in gravitational physics, such as cosmic acceleration or galaxy dynamics. If different theories predict distinct signatures, comparing these predictions with observations offers a way to distinguish between competing theories. In this sense, searching for new physics through modified gravity is both a theoretical exploration and a bridge to observational science.

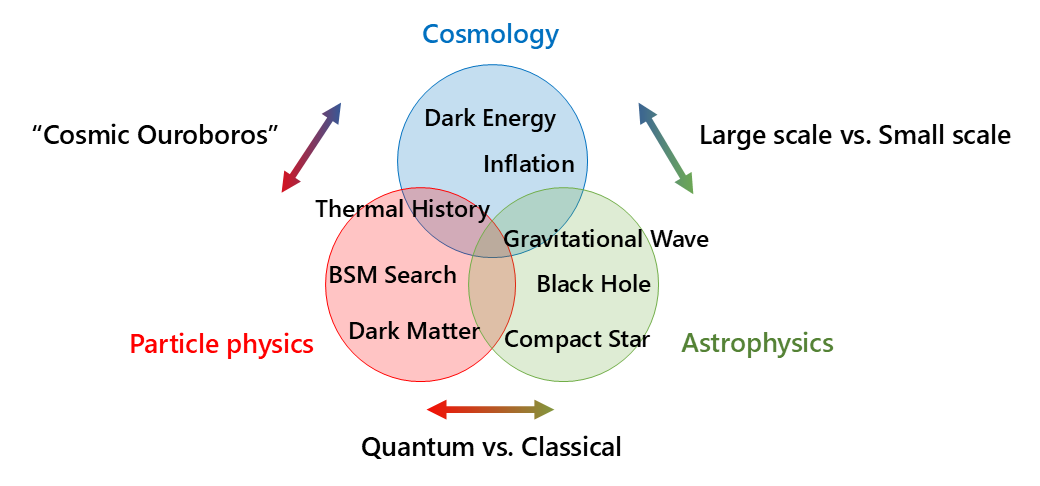

My work focuses on applying modified gravity theories to concrete physical contexts, including cosmology, astrophysics, and particle physics. By deriving theoretical predictions for how modified gravity differs from GR, I compare these results with existing and upcoming observational and experimental data. A major goal is to develop new theoretical tools that can clearly differentiate between gravitational theories using physical observables and measurements.

(Click or tap the figure to enlarge.)

Beyond the General Relativity

Mysteries in our Universe

In physics, we recognize four fundamental forces: the electromagnetic, weak, and strong forces — described by the Standard Model (SM) of particle physics within the framework of Quantum Field Theory (QFT) — and gravity described by GR. Although both the SM and GR have achieved remarkable success in explaining phenomena across particle physics and gravitation, several major observations remain unexplained.

Observations of Type Ia supernovae and large-scale structure indicate that the expansion of the late-time Universe is accelerating. To account for this acceleration, we postulate the existence of dark energy (DE), a form of energy with negative pressure that drives the accelerated expansion. In addition, measurements of galaxy rotation curves, gravitational lensing, and other astrophysical data reveal the presence of dark matter (DM) — matter that does not interact with light but exerts gravitational influence.

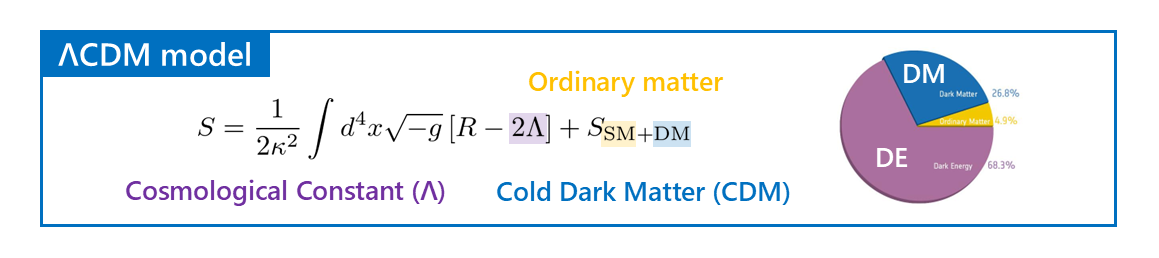

Recent cosmological measurements suggest that ordinary matter (atoms and stars) makes up only about 5 % of the universe’s energy budget, while DM and DE comprise approximately 27 % and 68 %, respectively. This dark side of the universe (DSU) dominates the cosmos, yet remains poorly understood. It is one of the central mysteries of modern physics.

DE and Cosmological Constant Problems

The standard cosmological model, known as ΛCDM model, incorporates a cosmological constant Λ to model dark energy and cold dark matter (CDM) to represent the dominant form of matter in the Universe, all within the framework of GR. This model successfully reproduces most features of the cosmic expansion history and structure formation.

However, it faces two fundamental theoretical challenges related to the cosmological constant:

- Fine-tuning problem: Observations indicate that the value of the cosmological constant is extremely small — about 120 orders of magnitude smaller than what naive QFT estimates of vacuum energy would predict. Any mechanism that cancels this discrepancy must do so with extraordinary precision.

- Coincidence problem: Not only the cosmological constant is small, but its energy density today happens to be comparable to the combined energy density of matter (DM and ordinary matter). There is no clear theoretical reason why these energy densities should coincide at the present epoch.

Beyond DE Problem

Motivated by the profound DE problem, extensive studies in modified gravity have explored whether cosmic acceleration can be reinterpreted or dynamically generated without invoking an extremely fine-tuned cosmological constant. At the same time, research on modified gravity has also developed across a wide range of research areas, including cosmology (both the late-time and early Universe), astrophysics, particle physics, and quantum gravity.

(Click or tap the figure to enlarge.)

Why Modified Gravity?

The following subsections describe motivations for modified gravity in different physical regimes.

For Late-time Universe

Although ΛCDM model successfully fits much of observational data, it does not resolve the theoretical issues described above. This motivates the search for new paradigms in gravitational physics. Modified gravity theories provide such alternatives by altering the gravitational action — replacing or extending the Einstein–Hilbert action of GR with generalized forms that introduce new dynamical degrees of freedom expressed by dynamical fields.

If these new fields behaves similarly to a cosmological constant and dynamically drives accelerated expansion, it may explain the late-time cosmic acceleration without requiring an extraordinarily small constant. In this way, the fine-tuning problem becomes a question about dynamical DE fields. These alternative mechanisms offer an intriguing route to addressing DE and motivate cosmological applications of modified gravity.

For Early Universe

A viable gravitational theory must not only explain late-time acceleration but also be consistent with observations from the early universe. A well-known example is Starobinsky inflation, in which an R2 correction to the Einstein–Hilbert action naturally drives an early period of accelerated expansion without introducing an ad hoc inflaton field. Some modified gravity models are constructed so that they reduce to GR at small scales or high energies, ensuring consistency with early universe physics.

One prominent observational puzzle is the Hubble tension: measurements of the Hubble constant H0 based on local (late-time) observations differ significantly — by about five standard deviations— from values inferred using early Universe data interpreted within the ΛCDM framework. This persistent discrepancy may suggest that our standard cosmological model requires modification. Cosmological models beyond ΛCDM model, including certain modified gravity theories, could potentially reconcile these differences by altering the physics of cosmic expansion at early times.

For Astrophysics

While DE is a phenomenon on cosmological scales, there are also astrophysical mysteries on smaller scales that challenge standard models. For instance, neutron stars with masses near two solar masses have been observed, pushing theories of dense matter and gravity to their limits. The internal structure of a compact star is determined by the balance between the internal pressure of matter and the attractive force of gravity. Explaining such massive neutron stars can proceed via three avenues:

- Modifying the equation of state of matter at high density and temperature (particle physics approach),

- Modifying gravity itself (gravitational physics approach), or

- Combining both new matter physics and new gravity physics.

Moreover, on scales smaller than about 1 Mpc and mass scales below roughly 1011 solar masses, the ΛCDM model exhibits discrepancies with observations. Examples include:

- Cusp/Core problem: observed DM distributions in galaxies are less centrally concentrated than predicted,

- Missing Satellites problem: far fewer small satellite galaxies exist than expected,

- Too-Big-to-Fail problem: the most massive predicted subhalos lack observed counterparts.

For Particle Physics

In many modified gravity frameworks, the additional fields that arise can be subject to quantization, leading to new particle-like excitations beyond those in the SM. This situation is similar to the semi-classical approach of quantum field theory on curved spacetime, where matter fields are quantized on a classical gravitational background.

Because these new particles originate in the gravity sector, their interactions with SM particles are typically suppressed by the Planck scale, making direct detection extremely challenging. However, this opens up intriguing possibilities for constraining modified gravity through particle physics experiments—such as high-energy colliders or precision ground-based observatories.

One particularly compelling scenario is that quantized fluctuations of a dynamical DE field might behave as DM particles, while the mean (background) value of the same field drives late-time cosmic acceleration. Such a unified framework of DSU — in which DM and DE share a common origin — offers a natural explanation for their relative energy densities, addressing the coincidence problem.

For Quantum Gravity

When extrapolated to extremely high energies — such as near the Big Bang or at the center of a black hole — GR predicts singularities where physical quantities diverge and the theory loses predictive power. This suggests that GR may be an effective theory valid up to a certain energy scale (the Planck scale) but incomplete at fundamental levels. A complete theory of quantum gravity (QG) is therefore needed to describe gravitational interactions at or beyond the Planck scale.

Attempts to quantize GR within the traditional framework of quantum field theory encounter severe difficulties, including unmanageable divergences. As a result, many alternative approaches to QG have been proposed, from string theory to loop quantum gravity. Rather than seeking a complete top-down theory, some researchers pursue a bottom-up approach, in which quantum corrections to GR at accessible energies provide clues about the underlying quantum gravity framework.

In this context, certain modified gravity theories can be interpreted as low-energy effective descriptions of QG, capturing aspects of quantum corrections while remaining tractable. Because this line of research is largely theoretical and far from experimental testability, current work focuses more on consistency checks and qualitative analysis than on making sharp observational predictions.

(Click or tap the figure to enlarge.)

Study on Modified Gravity

In pursuing the research directions outlined above, my work emphasizes how modified gravity models should be phenomenologically applied and theoretically understood across different physical contexts.

How to Use Modified Gravity?

Across all applications, what distinguishes a modified gravity theory from GR is the unique pattern of deviations it predicts. Careful theoretical analysis is required to calculate these deviations in specific physical contexts. As in all scientific inquiry, any new theoretical model must ultimately be confronted with observations and experiments.

Because gravity couples universally to all forms of matter, modifications to gravitational theory can, in principle, affect many areas of physics. Therefore, tests of modified gravity should not be limited to cosmological observations alone but should span astrophysics, particle physics, and even precision experiments in laboratories. This interdisciplinary perspective is essential for thoroughly evaluating the validity of any proposed modification of gravity.

Two Lessons

From a phenomenological perspective, deviations from GR provide the essential basis for testing modified gravity theories. Each model has unique additional degrees of freedom, which can produce distinct gravitational phenomena. From a theoretical perspective, these new degrees of freedom offer opportunities to explore physics beyond current understanding. They can broaden our theoretical understanding, opening new avenues for studying the interplay between gravity and other fields.

Two fundamental questions emerge from these viewpoints:

- How do the predictions of a modified gravity theory differ from those of GR? If matter fields themselves obey the SM of particle physics, then the modified gravity sector must account for all observable deviations from standard GR+SM physics.

- How can new degrees of freedom be employed to address unresolved issues? For example, additional fields may provide mechanisms for addressing DE or even behave as new particle species beyond the SM of particle physics.